The latest drones in Resolute’s Ontario woodland operations will help the company reduce its carbon footprint, and could even lead to faster forest regeneration after harvesting.

Those are just some of the strengths remote piloting systems, or drones, are bringing to work that is traditionally undertaken by planes and helicopters. “Both of which have a large carbon footprint, and both are expensive,” says Tom Ratz, Resolute’s planning manager in Ontario.

Drones are not new to forestry, or to Ratz, whose team of foresters have been using them for several years to do quick aerial inspections or fly them further afield to decide if they need to walk into an area with no road access, for example.

The newest models in the arsenal are bigger, faster, and more sophisticated than any of the other dozen drones the team currently uses. In fact, given their size, weight, and speed, these drones are operated by a specially trained and licensed pilot, whose work includes mapping flight plans and processing the images the drone cameras capture.

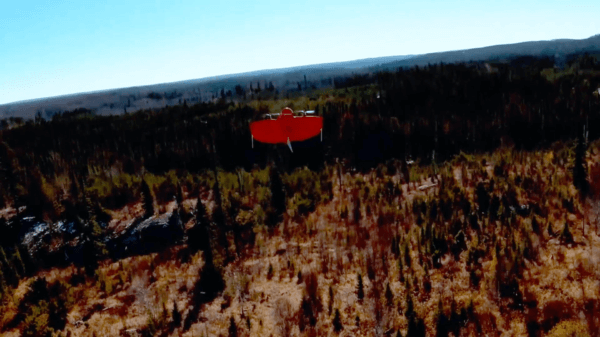

The seeding drone, a Hylio AG-166, is a heavy-duty multicopter. Built in Texas and designed as an aerial sprayer, the drone’s sprayer arms were removed and fitted with a seed spreader. Loaded with jack pine seeds, the drone flies like a helicopter and can get to work right after an area has been harvested, allowing seeds to germinate along with other species.

This fall the Hylio drone is finishing a few more weeks of production testing to gather enough information so that it can be used to seed this spring. While relatively new in Ontario reforestation, seeding drones have been used with success in Canada and the U.S. in areas affected by wildfires.

High-resolution, current forest imagery

Before seeding can begin, the team needs an accurate, detailed, and current picture of the area. Enter the WingtraOne, a drone that flies like a plane (at 35 mph – 57 kilometers per hour – it is eight times faster than a multicopter) and can takeoff and land vertically.

The Swiss-made WingtraOne was purchased from the Thunder Bay-based Four Rivers Group, the first Indigenous Wingtra dealer. In fact, both drone purchases benefited from partial funding by CRIBE – the Centre for Research & Innovation in the Bio-Economy, in part for how drones help reduce carbon emissions and because this initiative brings innovative technology into the forest products industry.

Equipped with a high-resolution camera and a four-foot (125 cm) wingspan, the WingtraOne can fly in a series of parallel tracks that are then stitched together to form a detailed photograph.

“You can literally count the logs in this image,” Ratz explains of a cut block displayed on his monitor. “I can tell what’s pine, what’s birch. I can see if there are any missed pieces.”

Satellite images are often used for this purpose, but you would not get the resolution these provide, says Ratz. And while planes provide higher resolution images, the cost of using one has increased by 20% in the last year.

Beyond depletion mapping, the drones are also used to help pulp and paper mills inventory their wood chip stores. Ratz also hopes to combine the drone’s high-res image capture technology with specialized software that could recognize and count tree species so that Resolute can continually update its forest inventory information.

Finding hot spots with thermal imaging

The WingtraOne’s high-end compact Sony camera can be switched for a thermal imaging camera that can check pulp mill wood chip stores for hot spots. As piles of chips and biomasss compress, they can generate enough heat to lead to combustion, making the drone an important part of a mill’s safety system.

The thermal camera can also check on areas where a controlled burn was used to reduce debris at roadside. The drone can easily recheck the same area to make sure there is no lasting fire.

Each new application seems to generate new ideas on how to use these new tools.